On April 15, 2020, Ruth Young Tyler’s employer called to say her services “were no longer needed.”

Suddenly, she was an out-of-work marketing manager.

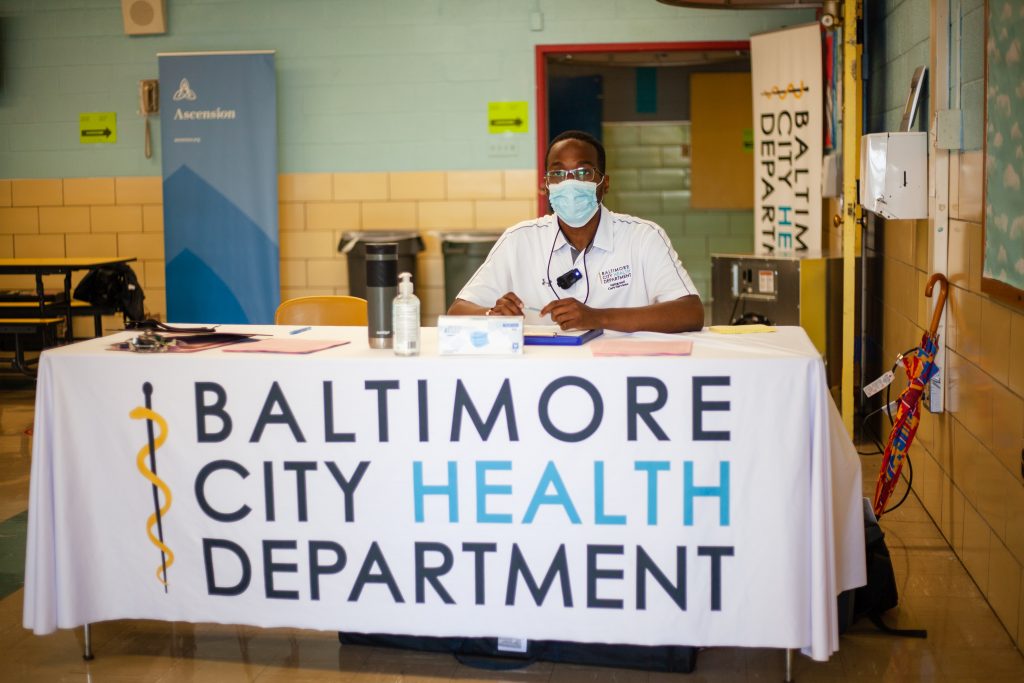

As Ruth will attest, there was a surprising upside to losing that job. The Baltimore City Health Department suddenly did need her services—not least her energy, empathy and well-honed communications skills. It was looking to hire Baltimoreans who had lost jobs to COVID-19 and offering to train them for sustainable employment on the frontlines of public health.

In the early days of the pandemic, contact tracing was in big demand and contact tracers in short supply. That’s when the city’s Health Department first called on Jhpiego—the Johns Hopkins University global health affiliate with almost half a century of expertise in hiring, training and supervising community health workforces around the world. With the support of these local partners in health, as well as the mayor’s Office of Employment Development, HealthCare Access Maryland and The Rockefeller Foundation, a nascent Baltimore Health Corps (BHC) took shape.

Originally consisting largely of contact tracers,—meet four whose stories Jhpiego shared in December—the BHC has grown this past year. It has adapted and evolved in response to a variety of community needs and priorities that shifted and expanded as the COVID-19 crisis peaked in the spring and now has entered a new phase. With safe vaccines widely available, local schools and businesses are open, but the highly transmissible Delta variant and its impact on unvaccinated residents threaten to upend some of the hard progress made in tamping down this pandemic.

In addition to contact tracing, BHC employees are now out and about, supporting the Baltimore City Health Department COVAX Call Center, mobile testing sites and vaccine clinics to serve city residents no matter where they live or if they are experiencing homelessness. The BHC is as determined to connect people in need with social services and health resources as it is to investigate outbreaks of COVID-19.

“This community health work is so important, not only to continue fighting COVID-19 through our mobile vaccination clinics, outreach and education, but also for continued preparedness against future diseases,” says epidemiologist Kristina Grabbe, a senior technical advisor for Jhpiego who has led a critical part of the larger BHC initiative to hire and train hundreds of out-of-work Baltimoreans. “We hope this workforce will have a lasting career and impact in Baltimore City, and that we will have an opportunity to continue developing their skills with other disease investigation as the needs continue to change and develop.”

Along with Ruth, a care coordinator for HealthCare Access Maryland whose story you can hear by clicking this link , meet Barellie Thompson, a mobile vaccine response team member and site lead; Teresa Gonzalez-Rivera, a call center agent and community health worker; and D. Layne Humphrey, a COVID-19 outbreak investigation manager. Along with dozens of their colleagues, whose former careers also had been claimed by COVID-19, these four practitioners of public health constitute the new face of the BHC, one that’s both fresh and familiar.

Listen to our podcast, “Ruth Redefined”

Setting the Vaccine Scene

Born and raised in Baltimore, Barellie Thompson, 25, is described by BHC staff as a “contact-tracer-turned-star-mobile-vax-site-lead.” No small praise there.

Trained and hired in December 2020 to do contact tracing, he joined the mobile vaccine response team in March of this year.

“I prefer this type of work,” he says, explaining that he enjoys the direct contact he now has with people who generally are grateful and relieved to get vaccinated. As a contact tracer, the focus of his work was on phone calls informing individuals they’d been exposed to COVID-19 and recommending quarantine. Previously he’d refer his contacts to resources to assist with isolation or quarantine, over the last several months he transitioned to a community-based team providing vaccinations. Now Barellie is part of the front-line staff that guarantees people will get what they need right away, whether it’s their first or second shot.

Barellie supports a network of clinical partners, who work with the Health Department, by making sure that mobile vaccine clinics run smoothly. He leads a team that sets up sites across the city at senior centers, churches, community sites, homeless shelters, drug treatment centers and public housing. They handle all the supportive logistics according to proper protocol; everything from consent forms and documentation to flow of traffic.

A graduate of the University of Maryland Baltimore County, pre-pandemic, Barellie worked as a behavioral aide at Creative City Public Charter School in west Baltimore. It was a foot in the door to a career in education, which was his dream. When schools closed, he found work at a local dollar store, “which was completely unrelated to what I want to do.”

A resident of northeast Baltimore, Barellie is happy to ease the concerns of people he meets at vaccine clinics by telling them he got the shot, and yeah, had a sore arm. If they have medical questions, he’ll introduce them to a nurse on site. He recognizes when someone’s on the fence and feels that “people will come down off their fears once they’re ready.”

As an employee of the BHC, he’s proud to be part of a team of compassionate people who do their best to help others and make them feel safe and comfortable.

“I wouldn’t mind staying with the Health Department [after the pandemic is over] … in community health outreach or something like that,” he says. “That would be dope.”

Las Madres Saben Que Es Lo Major (Mother Knows Best)

Teresa Gonzalea-Rivera loves working as a BHC call center employee, fielding incoming calls from Spanish- and English-speaking city residents, giving out information about COVID-19, providing resources, linking people to test sites and registering people for mobile vaccine appointments.

Originally from Puerto Rico, where she earned a bachelor’s degree in accounting, Teresa found her true calling—serving people—when she moved here with her two young children in 2006 to be with her husband, who works for the Baltimore City Police Department.

First, she found work as a caregiver for an elderly woman and later volunteered at her kids’ public school. That turned into a part-time teaching position, which lasted until the pandemic shut down schools.

After just a short time being unemployed, she joined the BHC when the city offered her a job in December 2020. These days, the 47-year-old mother of two and grandmother of a one-year-old is happily and gratefully serving her community. For example, the Spanish-speaker who called in worried about his wife, baby and toddler, all of whom tested positive for COVID-19. His baby girl had lost her appetite, he said, and wanted only to breastfeed; his wife, feverish and coughing, was exhausted.

Language can present a major barrier to tamping down the pandemic, Teresa says. She speaks with many Spanish-speaking residents who often don’t know what to do about quarantine or isolation, or how, where and when to seek care. Being able to respond to callers in their own language is helpful for giving comfort to those in need and building trust in the Health Department.

“That call touched my heart,” she says. “I asked if he had medical insurance, and he doesn’t. I referred him to HealthCare Access Maryland, which provides assistance to those who are uninsured. And, also, to a place that delivers food for those who test positive for COVID-19.

“He was very grateful.”

Then there was the senior citizen who called to say she had made an appointment online to get vaccinated, but mistakenly deleted the reply message indicating the date and time. She was frantic until Teresa helped her to recover the lost confirmation from her email trash.

For these callers, as well as her neighbors and family, she’s the go-to person when it comes to issues related to COVID-19. Teresa’s not shy about telling her 24-year old son, an Air Force guard in Florida, to “wear your mask, social distance, wash your hands!” even if others are more relaxed about prevention measures.

As a mother, she will do—or say—what’s necessary to keep her kids safe.

An Empathetic Investigator

As a team lead for investigating outbreaks of COVID-19 at local institutions throughout the city, D. Layne Humphrey has grown accustomed in the past seven months to having challenging conversations. Talking with business owners and other community leaders about possible COVID-19 outbreaks at their facilities is not easy, and people can be sensitive when you mention that their employees may have been exposed to COVID-19.

Yet outbreak investigation is a critical component of the city’s COVID-19 mitigation response, and one that Layne takes seriously. When new COVID-19 cases have been detected and there is a concern it could lead to an outbreak, Layne and her team of investigators are quick to respond and navigate the complexities of having these hard conversations with community organizations and businesses.

“I mean, you just keep saying what you know you need to say even when it’s uncomfortable,” says Layne, a lifelong Baltimorean who spent 25 years managing research.

Most organizations and businesses that Layne works with are eager to comply with regulations and evidence-based guidance, and welcome the support of the Health Department. Layne thinks fondly about her partnerships with local businesses—citing examples of helping owners make plans for controlling a current outbreak, for communicating with their staff, or for changing their workflows to prevent future outbreaks; she refers to these as examples of “beautiful cooperation.” For instance, when one business owner expressed concern about possible COVID-19 exposure to his staff, she was able to reassure him and they developed a plan for keeping his staff safe and healthy, now and in the future. “In the end it was a good conversation and he thanked me several times for listening and trying to help,” she says.

Outbreak investigation was among the first of the COVID-19 mitigation efforts taken up by the Health Department in an effort to contain and control the spread of the deadly virus, often among the city’s most vulnerable populations.

“This has always been an essential part of the Health Department’s work, but by expanding the outbreak investigation team to include BHC staff such as Layne, we were able to build additional capacity within the team to respond more quickly and effectively to outbreaks throughout the city, while also enhancing the diversity of our workforce and giving more employment opportunities to city residents,” says Anna Schauer, Director for Case Investigation and Contact Tracing, who also oversees the BHC at the Health Department.

Lately, Layne spends more time identifying businesses and agencies where onsite vaccine clinics might be appropriate and linking the city’s mobile response team with those sites.

“If you grew up in Baltimore City, you know people for whom [the pandemic] is secondary to eating, secondary to keeping a job, so that they don’t lose housing,” she says.

Layne recognizes the pressures many businesses are under and the economic issues they have faced. Recently, she too was stressed out; she needed to find work.

“Then I had the privilege of getting (this) wonderful job,” she says. “One that’s meaningful.”

Story reported and written by Maryalice Yakutchik. Photographs by Juliana Allen and Cole Bingham.