Waiting at Waita

Joyce Makasi was in the midst of a perfect storm of pregnancy and pandemic.

She was in labor, growing weak, and in need of a cesarean delivery. Daunting and dangerous as that situation might be in normal times for any woman living in in central Kenya’s Kitui Province, Joyce’s predicament was further complicated by a COVID-19-imposed curfew and lockdown, and a lack of personal protective equipment for health care workers.

Lifesaving surgical care was 70 kilometers away, down a rough road. Getting to a hospital in time seemed unlikely. Joyce already spent what money she had to hire the motor bike driver who brought her here to the clinic in Waita from her home in Kambiti village. And now she needed to go somewhere else again; to a facility with an operating theatre.

Terrified by the concurrence of complications, Joyce paced in pain for an hour, then two, and then three. Meanwhile, a nurse and clinical officer at the Waita clinic made call after frantic call, in search of a hospital that would dispatch an ambulance.

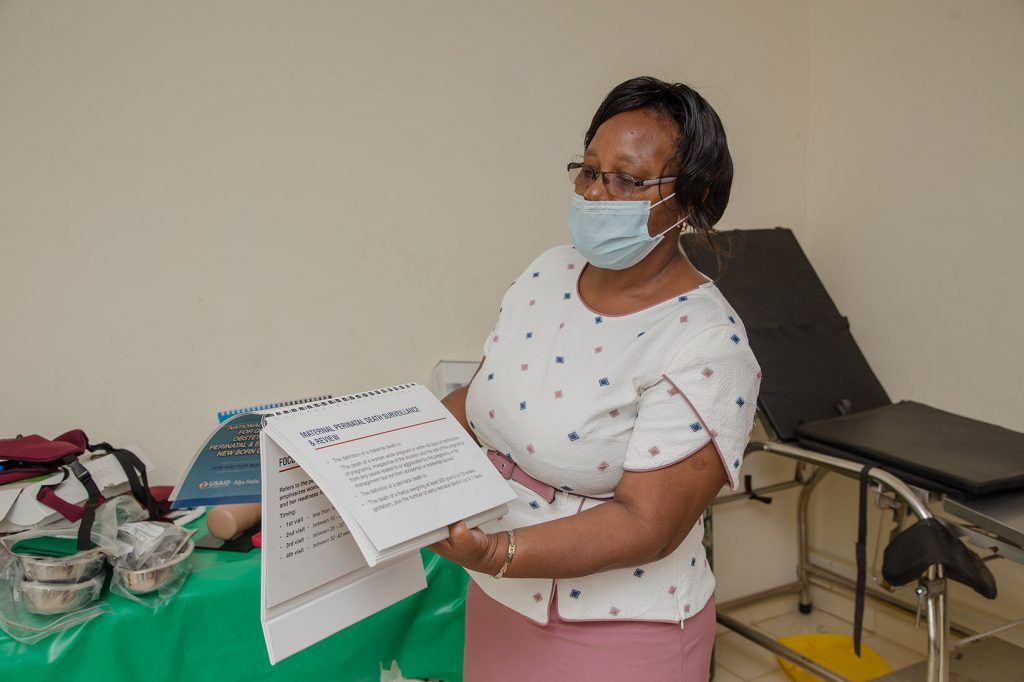

Triumphant at last, the nurse told Joyce to go home and wait for an ambulance that would take her to Tseikuru Hospital, an hour and a half away. The facility had a brand new operating room, built and equipped by the Kitui county government with support from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Afya Halisi project. As that project’s implementing partner, Jhpiego trained clinicians on the use of new equipment, including suction apparatus that can help babies in respiratory distress.

Dr. Solomon Orero, a gynecologist who served as Afya Halisi’s Chief of Party, not only taught medical officers surgical procedures such as cesarean delivery, but also worked with hospital management to ensure long-term sustainability of the measures after the project closed.

“The wait was not easy,” Joyce, 29, recalls. “I did not trust they would come.”

The Wait is Over

After a couple hours, the ambulance arrived as promised and Joyce received the evaluation and care she needed. The next morning, with the help of a newly competent and confident surgical team, Joyce delivered a healthy baby—on the very same day that County Governor Charity Ngilu officially opened the operating room where her cesarean was performed.

With great gratitude, Joyce named her daughter Charity.

Although the pandemic exacerbated the challenges Joyce faced, problems with transport and access to quality surgical care are longstanding and not uncommon in many low- and middle-income countries. Women in rural areas too often find themselves in dire situations during labor and delivery because of gaps in service, lack of social support for mothers and cultural norms that can inhibit them from seeking and receiving care during pregnancy.

Kenya had been making progress before the pandemic, but even then, just six in ten (62%) women who gave birth were attended by a skilled health worker. Maternal mortality was unacceptably high at 342 per 100,000 live births.

COVID-19 made a bad situation worse. A 2020 study modelling coverage of maternal and child health interventions during the pandemic estimates that in low- and middle-income countries, COVID-19 could cause maternal mortality to jump by anywhere from 8% to 39%.

Public health emergencies don’t preclude women from becoming pregnant and needing quality care that allows them to give birth in a dignified way. Every woman has the right to the highest attainable level of health, with the benefits of quality care extending well beyond her. As Jhpiego’s Koki Agarwal, director of MOMENTUM Country and Global Leadership, wrote in a recent blog, “Because a mother’s health affects the health of her entire family, it is critical that women continue to receive essential health services” such as quality antenatal care, delivery with a skilled birth attendant, breastfeeding support, and postnatal care.

As COVID-19 continues to shake even stable health systems and social networks, women everywhere need and deserve skilled, knowledgeable and equipped health workers like those who worked tirelessly to make sure that Joyce safely delivered baby Charity.

Verah Okeyo is the communications manager for Jhpiego in Kenya.