As a medical doctor with training and hands-on experience in infectious disease surveillance and emergency response, Ibrahim Seriki is the expert you need when developing a health plan for international borders—a critical but neglected area in global health security.

After several years as a hospital-based physician, Dr. Seriki wanted to expand his impact from individuals to communities. He embarked on a two-year field epidemiology training program led by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Nigeria. This took him to 29 of the country’s 36 states, where he gained extensive field experience in infectious disease surveillance and response. Upon completion of the program, Dr. Seriki led a World Health Organization joint vaccination program in Nigeria focused on measles and meningitis.

And then COVID-19 struck. With immunization programs paused and the pandemic calling for his expertise, Dr. Seriki headed to Lagos, the epicenter of COVID-19 in Nigeria. There, as a member of the COVID-19 response team, he supported the country’s surveillance efforts, including point-of-entry screening and testing.

This led him to Jhpiego Sierra Leone, where he leads the CDC-funded Enhancing Global Health Security project. Recently, he sat down with Jhpiego’s Joan Taylor to discuss this critically important work.

Q: What is border health and how does it protect people?

IS: We do many forms of screening in terms of immigration—customs to check goods you are coming in with, and immigration to check whether you are eligible to come into the country. Port health services include screening passengers for disease as they enter or leave a country.

But diseases do not recognize borders, crossing points or points of entry, so border health is not limited to screening, but also includes intensifying surveillance in the border communities and collaborating with neighboring countries on public health functions.

Ibrahim Seriki

It also includes risk communication, infection prevention and control, laboratory capacity for testing at the point of entry, and vaccination. As the International Health Regulations (IHR) (2005) outline, the point is to prevent the international spread of diseases. [The IHR (2005) is a legally binding agreement among 196 countries that defines how countries should respond to public health emergencies of international concern.]

Q: How does health security at land borders differ from health security at airports or seaports?

IS: The vast majority of travelers are crossing through the land borders—at both designated [those that meet IHR core capacities] and undesignated ground crossing points—not the airport. Only people who have money can afford to fly. Ground crossing points should get more attention when it comes to response. The risk of spread is evident from the Ebola outbreak in 2014/2015. The outbreak started in Guinea and affected all the neighboring countries because the communities are so interconnected, with vast population movement. The majority of people who pass through the crossing points live within the border communities, especially those informal crossing points that are not manned. So it’s necessary to intensify surveillance in the nearby health facilities—and ensure the supply of medical consumables.

Q: What are the main issues to consider when developing a border security plan?

IS: For border health generally, we are governed by the International Health Regulations. At the same time, we try to tailor the response plan to the locally accepted way of doing things. Then, of course, communication is key. You need to communicate to travelers why you’re doing this, what are the risks, what diseases are endemic in the visiting country. And there should be community engagement with border communities, because in some places people are crossing without [border] personnel for screening. Community stakeholders can play a role in supporting these unmanned crossing points.

Q: How do you prepare health workers and officials from different countries to work together and respond to an actual health emergency?

IS: You have to maintain collaboration over time. If there’s strong collaboration between countries, maybe through a formal agreement and information-sharing mechanism, then there can be a joint response because they’re used to doing things together. We initiated some level of collaboration during a regional tabletop exercise [a desktop simulation of an emergency response, such as a Lassa fever outbreak]. Our colleagues from Liberia and Guinea came to act as observers and evaluators, and we also went to Liberia to do the same. We’ve built some connections. To sustain that connection, we have to continue to do activities together. We’ve had regional meetings, as well, with the four countries in the Mano River Union region (Liberia, Guinea, Sierra Leone and Côte d’Ivoire) and binational meetings with Liberia.

We need joint cross-country plans, like the one we developed for Sierra Leone and Liberia during one of our cross-border meetings. Prediction and prevention of outbreaks will only be relevant if countries respond as one.

Every outbreak is a lesson. After the Ebola outbreak, diverse country coordination has been strengthened. Countries have learned how to mount an effective response to public health emergencies. The COVID-19 pandemic also provided an opportunity for the health security to be strengthened, despite language differences. For instance, Guinea has had recent disease outbreaks (especially viral hemorrhagic fevers) in the region. And they didn’t disappoint. They shared a lot of best practices. That’s the idea of these exercises—simulating a scenario and everybody gets to talk about how they would respond.

You can never stop preparing. It’s not cheap, but if you prepare very well, it will save you a lot more money if there is a pandemic or outbreak—and not just money, but lives lost. Preparedness helps reduce the money you’re spending when there’s an emergency. That’s why we have partnerships like The Pandemic Fund. The World Bank, Global Fund, everybody now wants to invest in preparedness.

Q: What other actions are you taking to support border health?

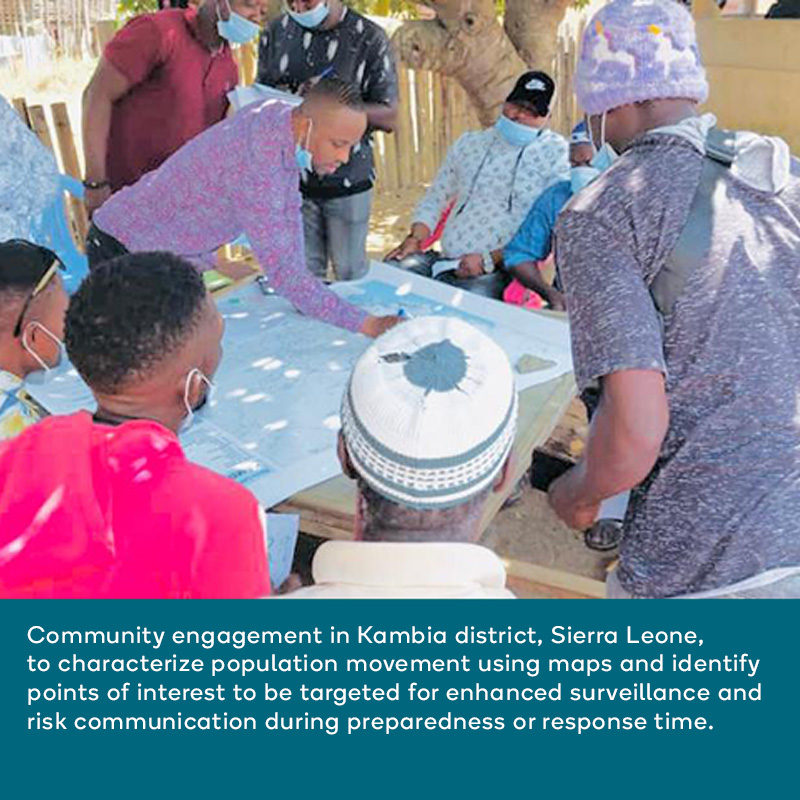

IS: Something we are doing uniquely here is population movement mapping in land border districts to identify areas with risk of disease transmission. This is a mixed-method study with qualitative focus group discussions and spatial analysis to identify where people frequent, including their point of entry and the reason for the visit. It could be for health care, for religious purposes, for schooling, or for markets. When we identify which areas are visited the most, we plan in terms of what to do if there’s an outbreak in the neighboring country, and make plans to allocate resources accordingly. During preparedness or silent periods, we can recommend that those places be strengthened for surveillance as well as risk communication. You can strengthen surveillance at the health facility. You can strengthen risk communication at the schools, at the market and at religious sites. You can also target the health facility for increased infection prevention supplies because they may be at more risk.

We are also supporting the Ministry of Health to develop a national border health policy. While the public health emergency response plan is meant for emergency settings, the border policy will guide both routine and emergency settings. The policy, based on the International Health Regulations, will detail the governance, components of the port health system and roles and responsibilities of the different sectors working in the national border health system. I don’t think any other country has this policy. We need to raise the bar.