Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire — From the moment Dr. Cyprien Nioble enters the Community Health Facility of Yopougon Wassakara, he is treated like a rock star. People call out greetings and wave to him as he walks by—everyone eager to get in a quick word with their former colleague.

One woman in her late 50s wearing a pink dress approaches the doctor and grasps his hand, saying to a visitor, “I’m alive thanks to this doctor.” She thought her life was over when years earlier she was diagnosed with HIV. Nioble, then the medical director at the facility, reassured her at the time that with proper treatment she would continue to live a full life. And she has. As the woman leaves Nioble’s side, she says to him, “I pray for you every morning.” The doctor smiles and adds, “Many people are praying for me.”

His focus, from early in his career until now, has been the clients. Nioble has worked alongside physicians, nurses and midwives to ensure that women and families receive high-quality health care.

On this particular day, Nioble is accompanying a group of his fellow Jhpiego colleagues from the Côte d’Ivoire office on a visit. As a member of Jhpiego’s country team, Nioble, a 52-year-old father of three, is the technical director of a national-level initiative, funded by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Jhpiego is supporting efforts to develop an integrated model for the management of chronic diseases, including HIV, with the ultimate aim to strengthen the national response to the HIV epidemic. The 5-year project is being implemented in more than 40 sites in two regions of the country.

As the medical chief of the bustling Wassakara health facility for 5 years, Nioble treated more than 700 patients living with HIV. He makes his way over to the facility’s unit for HIV and TB testing and treatment. In the cramped space of small offices divided by wooden partitions, two patients are being seen. One young man wears a mask over his face. Nioble talks with health worker Adela Kpan, who is speaking with a mother who came in to pick up her antiretroviral medication. On the wall above the desk, Nioble’s name and phone numbers are written in large letters in red marker. Kpan explains, “We call the doctor regularly for advice.”

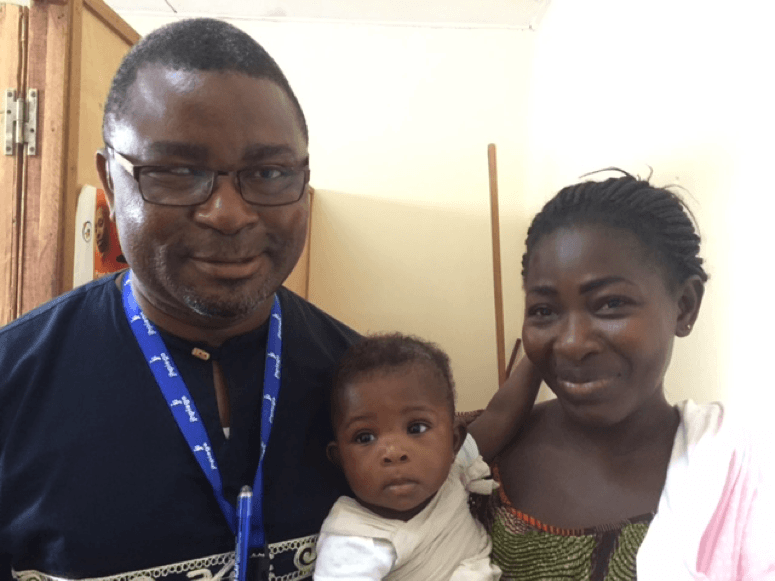

A mother holding her baby daughter walks into the office. Meita Touré smiles when she sees Nioble, who greets her warmly and pinches the baby’s cheeks. Touré, now 36 years old, was just 26 when she learned that she had HIV. Knowing that she was at risk of contracting HIV because of her profession as a beautician—a job that involves using sharp needles in hair weaves—she went regularly for testing. The diagnosis nonetheless came as a shock. Touré thought that her diagnosis meant that she could not have children. Nioble, her doctor at the time, reassured her that through treatment it was indeed possible. Today, Touré and her husband, who is HIV-negative, are the proud parents of two children—both HIV-negative.

Nioble relishes listening and talking with people. “Someone who has just been diagnosed with HIV needs support,” he says. In 2006, Nioble attended a 2-week Jhpiego training to develop quality standards for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV services. He was convinced by Jhpiego’s approach to improving services and trained his staff, saying, “Each individual had previously worked in his or her own way, but now we had a standardized approach and tool that everyone could follow.”

Nioble eventually was recruited to join the Jhpiego team in Côte d’Ivoire. He seized the opportunity to bring his skills in treating patients living with HIV to the national level and reach more of the country’s population with lifesaving health care services by building the capacity of his compatriots. To this end, the project is implementing the chronic care model in 44 health facilities; 45 providers have been trained in integrated management of chronic conditions, including HIV; 45 nurses and midwives have been trained to prescribe treatment to those living with HIV, something previously done by doctors; and nearly 5,000 home visits have been conducted by 100 trained community health workers for people living with chronic conditions.

Nioble knows that in this national capacity he can influence even more lives, saying, “Thousands of people have been saved thanks to the implementation of Jhpiego’s strategies. Our technical assistance saves the country’s health care system time and money through the sharing of best practices.”

Although Nioble is helping to lead the charge nationally with Jhpiego, he hasn’t let go of his community roots. “I became a doctor to help others stay healthy and live their best lives,” he says. “Our family’s name of Nioble … means take care of those around you.”