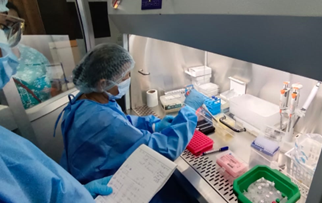

To prepare for and help prevent the next pandemic, global health leaders assert that countries need well-equipped laboratories and experts who are capable of detecting dangerous pathogens and new variants in time to respond. These labs need to be capable of genome sequencing—a technology that determines the DNA or RNA sequence of an organism, enabling its identification. Genome sequencing plays a crucial role in pandemic preparedness and response by providing valuable insights into the nature and spread of infectious diseases.

In India, the government recognized the need to enhance its genome sequencing capacity during the second wave of COVID-19 when only 28 next-generation sequencing (NGS) labs across the country were testing for new variants of the coronavirus in a country of 1.4 billion people. These 28 labs were not sufficient to accommodate all of India’s states and territories.

Genome sequencing labs are able to identify different pathogens that cause disease by analyzing their genetic code. By decoding the complete genetic information of a virus or pathogen, scientists can identify its unique characteristics, including how it spreads, mutates and interacts with human hosts. With this critical information, health officials can identify an organism that has potential to spread rapidly, endangering a community, and mobilize for an early response. But with COVID-19 cases rising during the COVID surges, the specialized labs couldn’t keep pace with the demand.

In partnership with the Ministry of Health, the U.S. Agency for International Development’s Reaching Impact, Saturation and Epidemic Control (RISE) project, led by Jhpiego, supported the government by rapidly establishing 11 new NGS labs across key locations in India.

“Setting up such a lab takes a lot,” says Dr. Rashmi Pillai, a microbiologist at Viral Research Diagnostic Laboratory at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences in Nagpur, Maharashtra, where one of the 11 NGS labs was established by RISE.

“Earlier, we were a basic lab, conducting RT-PCR tests and giving positive or negative results for COVID-19. The RISE team came in and gave us the necessary equipment. But beyond just the equipment, the team trained us from scratch, provided us with checklists, laboratory manuals, standard operating procedures and protocols that helped us set up the lab and made our team proficient in bioinformatics analysis [using computer technology to collect, store, analyze and disseminate genome sequencing results].

“Now, our lab is sequencing samples, and we are getting very good coverage. This has been possible because of the regular training from RISE. If any of us face a problem, we call the RISE team, and they help us right away. Our reporting mechanisms for genome sequencing have also been strengthened by the RISE team.”

The RISE project views COVID-19 mitigation work as, ideally, serving two purposes: addressing the immediate needs of the COVID-19 emergency and, simultaneously, preparing national health systems for future health emergencies. In India, the project works across 22 states, with the public and private sectors, to strengthen health systems through key intervention areas—delivery of critical care, vaccine coverage, access to medical oxygen and laboratory services.

Jhpiego’s Dr. Prashant Singh, who led the efforts to establish the NGS labs, believes that COVID-19 was not the first and will certainly not be the last pandemic the world will face. “Diagnostics is always the starting point for screening and managing any disease,” he says. “Therefore, these labs are critical, not just today but well into the future.” He explains further, “next-generation sequencing … has the capability of sequencing any disease-causing pathogen. We now have infrastructure in place and trained staff. We have the methodology. So, these labs can be used for testing any other new outbreak or disease—be it cancer, tuberculosis or other viral diseases.

Dr. Singh points to another big advantage of genome sequencing, the ability to track the emergence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which the World Health Organization defines as a microorganism’s resistance to a drug that was once able to treat an infection by that microorganism. India is becoming an epicenter of AMR, causing an estimated 700,000 deaths a year.

With the rapid increase in AMR, one fears the day when even a simple bacterial infection will become untreatable. NGS can help identify and discover antibiotic resistant genes in bacteria, which allows providers to choose the right antibiotic treatment, analogous to precision medicine.”

Dr. Singh

Creating this awareness about the long-term benefits of these labs is key, states Dr. Singh. “We are conducting consultative workshops, bringing state administrators, key opinion leaders, technical experts, and public health officials to deliberate on the importance of genome sequencing,” he says. “By disseminating sequencing best practices across RISE-supported states and providing guidance on the use of sequencing labs to detect other pathogens post COVID-19, our hope is that public sector laboratories will be quick to detect and manage any future surges of infectious diseases.”

Both Doctors Singh and Pillai share a common vision for the future. In the words of Dr. Pillai, “We look forward to a day when genome sequencing facilities, just like point-of-care diagnostics, can reach every corner of our country, so that diseases can be caught early, even from the most remote and hard-to-reach areas. This will save many, many lives.”

Dr. Bhakti Hansoti, MBChB, PhD, MPH, RISE Technical Director, provided technical review on this article.

Indrani Kashyap is Jhpiego’s Associate Director, Regional Communications; she is based in India. Pankhuri Shukla, a Communications and Documentation Officer in Jhpiego’s India office, also contributed to this article.